In the heart of the East Texas Community of Pineland, Texas, sits Georgia-Pacific Corporation, one of the world’s leading makers of tissue, pulp, packaging, and building products.

Like many manufacturers, Georgia-Pacific constantly looks to have a pipeline of qualified semi-truck drivers ready to fill openings. The reason is simple: commercial truck driving is one of the most in-demand positions in the United States.

Through a partnership with Lamar State College – Port Arthur, the Pineland community realized an opportunity to have driving training locally. So, the community is looking at starting a truck driving school.

To get clearance to pave a lot and make a driving obstacle course, the Texas Historical Commission (THC) required a Phase Archaeological Excavation. The early stages of that excavation began on March 6, 2024, where Communities Unlimited (CU) partnered with the City of Pineland and Lamar State College – Port Arthur to assist on the project.

“This school creates a chance for Pineland’s truck drivers to live local, train local, work local,” said Martha Claire Bullen, CU’s Director of Community Sustainability (CS). “But it also, subsequently, adds to the pool of skilled drivers that will be in the market for some of the OTR (over the road) positions if that is interesting to a graduate.”

Not only was Bullen involved in the project, but CS Area Director Michelle Viney and Community Resource Manager Kristy Bice were in attendance. CU’s Geographic Information Systems (GIS) team of Don Becker (coordinator) and Harrison Brown (specialist) helped on the archaeological side.

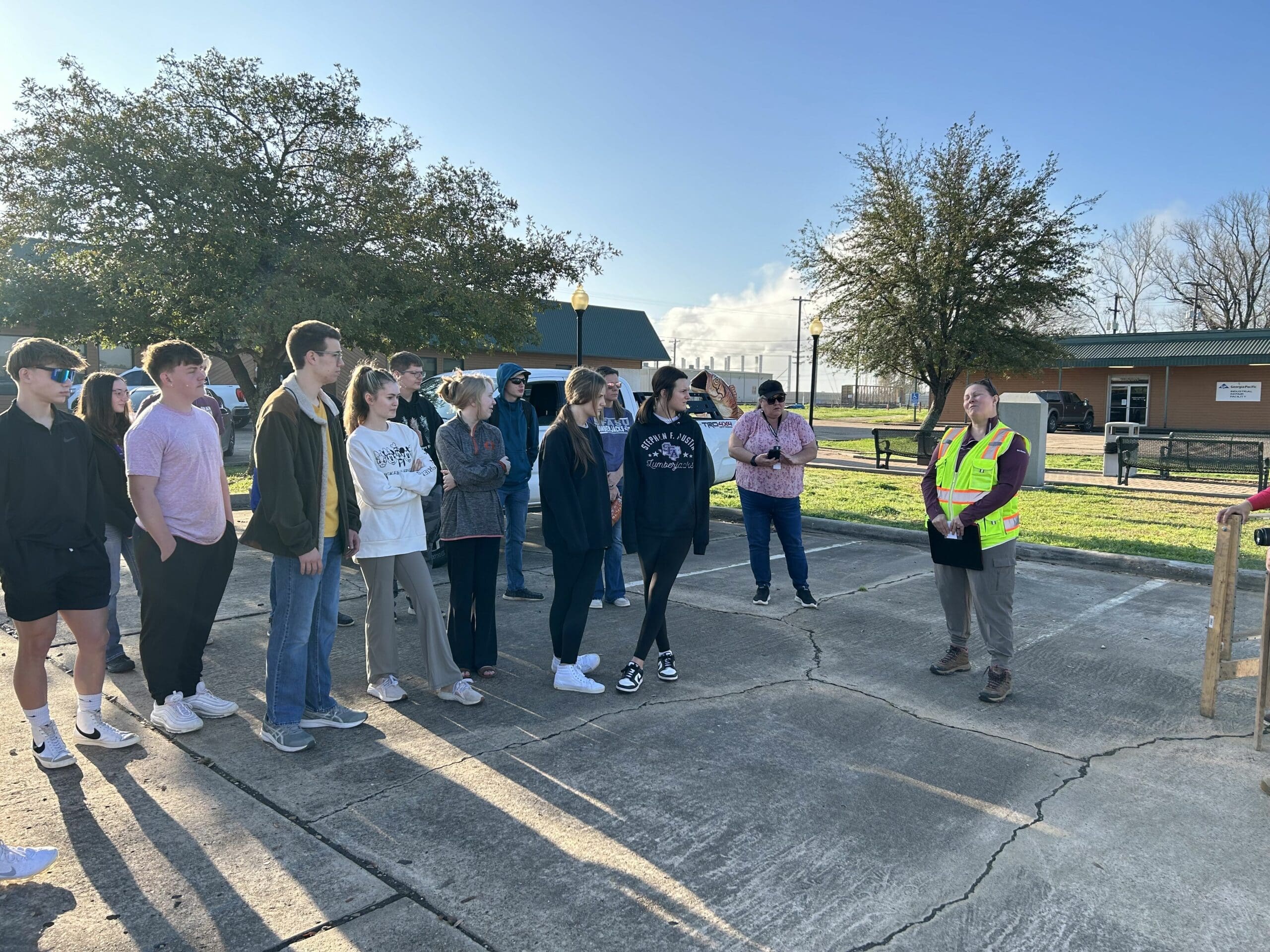

The excavation required sample holes to be dug on the lot to evaluate what was going on below ground surface, ensuring no cultural resources would not impact development in that space. Becker and Brown collaborated with Texas State University archaeologists Erin Hamilton and Hilda Torres, while science club students from local West Sabine High School took part in the exploration.

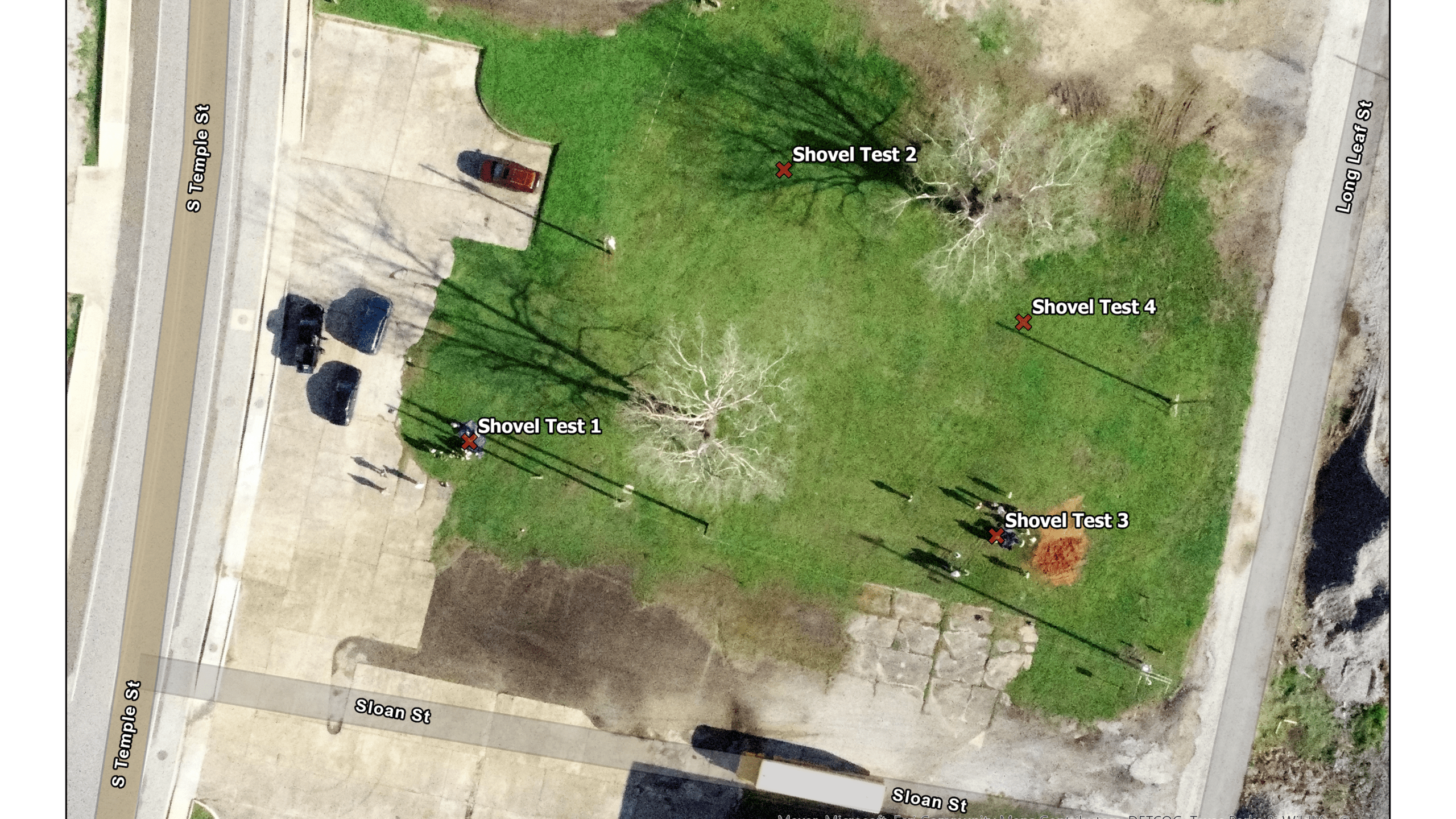

The group was broken into two teams. They wound up digging four holes in total, and the excavation process entailed passing soil that came out of the hole through a screen to look for artifacts – something manmade or modified by humans.

Their objective was to look for evidence on what happened on the lot in the 110-year history of urbanization at the location and whether there are impact cultural deposits below the ground surface.

Once the hole was excavated completely, the artifacts were removed, examined, and all the soil was put back in the hole. They then replaced the grass on top, almost as if nothing ever happened.

Hamilton and Torres managed the scientific aspect of the project in the East Texas community, processing the contents of each hole and meticulously documenting everything that came out of the hole. For example, Hamilton took measurements of how deep soil changes occur. There are different layers of soil below the surface, and they grouped the artifacts by which layer they came out of with the intent to keep things separated.

Hamilton enjoyed the entire project, and getting to work with students made it special. She said one of Centers for College of Studies missions is to provide public outreach to communities and inform the next generation about archaeology of Texas.

“That was something we were happy to provide them,” Hamilton said. “It was great. It was cool to see kids interested in science and what I have spent my life doing. That was a lot of fun.”

Following the excavation, Brown captured several different drone photographs to generate high-resolution imagery of the lot with the four sample holes shown. There was a mix of artifacts in three of the holes, consisting of brick pieces, metal objects like nails, bottled glasses, and more.

Shovel Test 4 was the most interesting, Becker says. It did not have a lot of artifacts but had a concrete block that sat at an angle. The piece went all the way across the bottom of the hole and stopped further excavation. This hole was much shallower than the others. According to Becker, concrete blocks are likely part of a building footing.

The archaeological investigation process involves three phases. It currently remains in Phase 1 as the THC hasn’t yet reported about the findings. THC may ask for a Phase 2 to get further investigation of the lot. If they don’t think it warrants further investigation, they will just approve the report and construction can get underway.

This was certainly a memorable project for members of CU.

“It was amazing because we got to bring our CS team and our GIS teams to this East Texas community,” Bullen said. “Students got to learn about archeology and mapping and CU as a whole organization. It was so fun to create a real learning experience for these students.”

Becker explained this GIS project was a fun departure from typical infrastructure mapping projects.

“This project was a great opportunity for CU GIS Staff to make a modest contribution to the cultural resource documentation for Pineland, Texas,” Becker said.

Brown said he remembered at one point after flying the drone and digging a hole, he looked to Becker and said, “We’re getting paid right now?” He not only introduced the high school students to GIS technology but drone tech as well.

“These are the types of projects that make me love my job,” Brown said. “They feel to me more like having fun on a school field trip than working. The kids in Pineland surprised me. I expected them to be at least a little interested, but they were fully invested in every aspect of what we were doing. I think the project was informative for them, and I think they had a lot of fun.”

Pineland, an East Texas community located in Sabine County, is within the 24-county region where the T.L.L Temple Foundation and CU are working together. CU and the T.L.L Temple Foundation created a model to assist rural communities called, “Connect Rural, Assist Rural, Lead Rural” that they have been working on for two years. Program officer Jerry Kenney represented T.L.L Temple at the event.

"At its heart, rural development is about connections. This Pineland archeological dig represents how our future prosperity is always connected to our past. It's an example of how we can engage the next generation of rural leaders in finding solutions to the challenges facing rural East Texas communities today. Through these connections and engagement, digging up the past becomes a chance to plant the seeds of a thriving future."

— Jerry Kenney, Program Officer, T.L.L Temple Foundation

“It was exciting to witness firsthand the power of partnerships driving this project forward in Pineland, particularly Lamar State College Port Arthur, West Sabine I.S.D., and Communities Unlimited. I’m proud of the T.L.L. Temple Foundation’s role in activating and strengthening these partnerships.”

Bullen echoed Kenney, saying the amazing thing about this Pineland project was the creativity to take on what could have been just a box being checked for a federal agency to survey land prior to a build became an opportunity to bring partners together in East Texas, including high school students.

“Who knows?” Bullen asked. “Maybe the next great archeologist was born that day while learning about soil layers.”