In this small East Texas town, where pine trees tower over winding roads and neighbors still greet each other by name, the homes tell a quieter, more urgent story — one of aging structures, storm-damaged roofs, and limited resources.

Recently, Communities Unlimited (CU) launched a housing outreach effort in Alto to connect residents with the Fortified Roof Program, a no-cost initiative designed to help homeowners strengthen their roofs against high winds and extreme weather. Backed by City Councilman Luke Johnson and led on the ground by Kristy Bice of CU’s Community Sustainability Team, the campaign was personal and direct: Bice went door to door, talking with residents, filling out paperwork, and guiding them through the process. Bringing programs like this to life takes more than funding — it takes local expertise and boots-on-the-ground relationships that build trust and get results.

In the end, 14 households submitted completed applications — a promising number in a town of just over 1,000 people.

But not a single one qualified.

The problem wasn’t red tape or income limits — it was the homes themselves. Many were so deteriorated that adding a fortified roof would have posed more danger than protection. Foundations were unstable. Roof decking had rotted away. Walls had shifted after years of storms and patchwork repairs. In many cases, the very poverty that made residents eligible for help had also left their homes ineligible for repair.

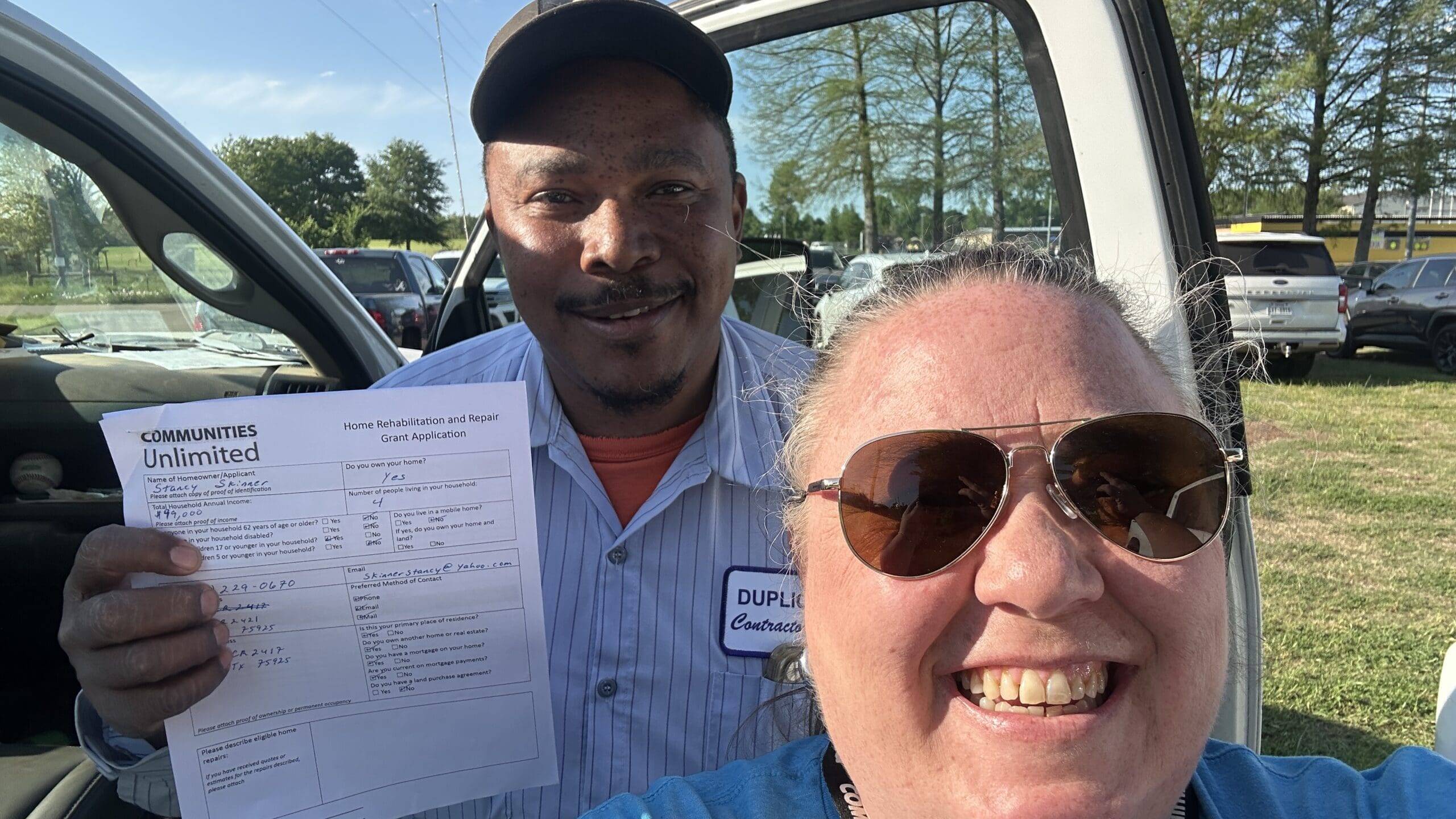

Margie Skinner’s story is one example. A resident since 2019, she lost her first home to a tornado. Her current home has had its roof torn off twice by storms — the most recent damage occurring just after she repaired the first half. “After that, it started raining inside the house,” she said. The Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) denied her requests for assistance twice.

Margie didn’t qualify for CU’s Fortified Roof Program, but a connection was established, and there’s hope she could benefit from future home repair efforts. “At least with Kristy and you all, someone came out and talked to us,” Margie said. “That meant something.”

The Fortified Roof Program — developed by the Insurance Institute for Business & Home Safety (IBHS) — is designed to protect homes from severe weather using sealed roof decks, reinforced fasteners, and other upgrades that exceed standard repairs. In disaster-prone regions, these improvements are quickly becoming the norm and can even lower insurance premiums. But they rely on a solid foundation to begin with, making them inaccessible for homeowners whose properties have already suffered decades of neglect.

Part of the challenge lies in the age of the homes themselves. Three out of four homes in Alto were built prior to 1989 — and older homes are far more likely to require costly repairs, resulting in substandard housing and unsafe living conditions. Over time, without the resources to make needed upgrades, these structures have fallen deeper into disrepair.

Councilman Johnson said the outreach, while discouraging in its immediate results, revealed something critical.

“It shed light on the deeper housing challenges facing Alto: the aging condition of many homes, the prevalence of substandard structures, and the reality that too many of our residents live in homes in need of major repair or full replacement.”

— Luke Johnson, Alto City Councilman

The campaign came just as CU’s Housing Team expanded into East Texas — a move formalized in October 2024 through a cooperative agreement with USDA Rural Development. This work was supported on the ground by CU’s CS Team, whose efforts in the region are supported by the T.L.L. Temple Foundation. Alto, located in Cherokee County, was one of the first communities to receive targeted assistance.

Although the USDA agreement was later discontinued amid federal changes, CU has continued its housing work in East Texas — funding it out of limited core resources due to the overwhelming need. The organization is actively seeking philanthropic support to help sustain and grow this work in communities like Alto.

“We are losing rural homes faster than we can replace them, and many of our rural communities and neighbors lack resources and funds to address this need on their own. It costs more to build and repair homes in rural areas than in urban areas — and that’s only after you find a contractor, sub-contractor, or developer willing to work in the area. Just like the residents we serve, we face challenges too — especially when it comes to funding. We want to broaden the reach of our housing work here, but without additional support, it’s difficult to scale. The need is clear. We see it every day.”

— Audra Butler, CU Area Director of Rural Housing

The need is also deeply personal.

Larry Roark, who spent years traveling and working overseas as a diesel instructor, returned to Alto to remodel the house his grandmother left behind. After undergoing spinal surgery and relearning how to walk, he still climbed onto his roof to tarp a hole after a storm punched a limb through it.

“I had trouble getting down the ladder — I almost fell,” he recalled. “I haven’t been back up since.”

Although his home didn’t qualify for a fortified roof, Roark was later approved for a new roof through CU’s COME HOME Repair initiative, which assists homeowners with deeper structural issues. The roof is scheduled to be installed in the coming weeks. Still, the upgrade lacks the high-wind protections that fortified roofs offer — including sealed decking and reinforced attachments that can make the difference in a major storm.

For others, like Virginia Olvera, the issues are just as urgent. She lives in a trailer home where water pours in when it rains, damaging the ceiling and shifting the foundation blocks beneath the structure.

“The whole house moves,” she said. “We really need help leveling it, too.”

Though she didn’t receive assistance through the Fortified Roof Program, Olvera said the outreach helped raise awareness of just how urgent the need is.

“I’ve had to miss time from work because of the condition of my house.”

Roark added that many homes in Alto face similar challenges — not just with roofs, but with windows and other basic structural needs. He’s seen neighbors use plexiglass to replace broken window panes because the originals were too worn or too costly to repair. Many of the town’s older homes also lack proper insulation, making it difficult to keep them warm in the winter or cool in the summer. After recent tornadoes, roof damage became widespread — but for families living paycheck to paycheck, repairs were often out of reach.

“Some people would have to sell their car or mortgage their home just to pay for a roof,” Roark said. “And if they fall behind, they risk losing everything.”

He spoke of neighbors living under tarps, raising grandkids while managing disabilities or surviving on low-wage jobs.

“What I’d like to see is more help for people who are doing the best they can. Getting a roof shouldn’t be such a struggle. A lot of people are working hard, paying taxes, and still feel like they’ve fallen through the cracks. It’s like cooking a brisket and everybody else eating it — and you don’t even get a sandwich.”

— Larry Roark, Alto Resident

While housing is the most visible challenge, Alto is actively investing in its future — including a $2.2 million upgrade to its water treatment plant, new Little League facilities, and downtown and road revitalization projects.

“These improvements lay the groundwork for long-term revitalization,” Johnson said. “But I believe the next critical need is housing — improving existing homes and incentivizing new, sustainable construction.”

He hopes to launch a structured support program that helps residents apply for resources — including assistance with income verification and paperwork — to increase access to repairs and even full home replacements.

Johnson also sees promise in CU’s broader COME HOME initiative, which explores modular housing, Accessory Dwelling Units (ADUs), and small-scale infill development. He plans to propose local policy changes that would legalize ADUs in single-family zones, encourage cottage housing and duplexes, pre-approve infill lot designs, and offer tax abatements to attract new housing.

“Given Alto’s central location among other rural communities with similar needs, we’re well positioned to serve as a regional model and multiply the impact of this work beyond our city limits if that ever becomes an option.”

— Luke Johnson

Meanwhile, CU continues to pursue that broader vision. Applications have been submitted to the Federal Home Loan Bank of Dallas for new housing funds, and the Housing Team is actively researching programs that support full-scale repair and replacement — going beyond what a roof alone can address.

While the Fortified Roof initiative didn’t result in new construction — at least not yet — it revealed something more important: the depth of the crisis. It gave voice to residents living under tarps and behind warped walls. It built trust. And it sparked momentum.

With a clearer view of the barriers — including homes too deteriorated to meet program requirements — Alto and other East Texas communities aren’t just applying for housing assistance. They’re working to build a foundation for lasting housing justice.