On a late afternoon at Jones Academy in Hartshorne, Oklahoma — a historic school in the Choctaw Nation — staff sifted through dusty boxes of maps and records. Few knew what lay buried in those papers, but with the help of Communities Unlimited (CU), they were uncovering something crucial: whether their drinking water was carried through lead pipes.

That search is part of a subcontract CU’s Community Infrastructure Team joined in August 2024 with Eastern Research Group (ERG) under an Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) initative to support utilities serving Native communities in Region 6, which includes Oklahoma, Texas, and Louisiana. CU was brought in through the Rural Community Assistance Corporation (RCAC), part of a national assistance network, because of its deep history working with tribal systems — particularly in Oklahoma, where 39 federally recognized tribes operate utilities across the state.

Lead Service Line Inventories

Lead is a major concern, especially for babies and children, because it affects brain development. When it enters drinking water, it doesn’t change the taste, smell, or color — so families may have no idea they’re being exposed. Even small amounts can build up in the body over time, slowing growth, harming learning ability, and causing lifelong health problems. For decades, lead was used in pipes because it was malleable and less likely to break. And even if the pipes themselves weren’t made of lead, the solder used in plumbing could still leach it into the water flowing into homes

The process is straightforward but labor-intensive: confirm what type of pipe connects each home or facility to the system. Anything installed after the federal lead ban in 1989 is assumed safe, but anything older must be checked. That means combing through old records, verifying installation dates, and sometimes even using maps or satellite images to estimate when houses were built.

In Region 6, ERG Senior Environmental Engineer Linda Hills said relatively little lead is turning up, but regulations require systems to confirm where lead exists — and where it doesn’t. CU staff worked alongside ERG to ensure inventories were completed and submitted, beginning with tribal systems and later expanding efforts to additional systems across Oklahoma that serve Native American populations. Many utilities had started the work but fell out of compliance by missing certifications or customer notifications. CU stepped in to close those gaps, guiding 19 systems through final submissions and helping another reduce “unknowns” through detailed records research. For many more, CU provided templates and step-by-step instructions so clerks and operators could finish the work confidently.

“I want operators and clerks to understand not just how to file the paperwork, but why it matters,” Harmon said.

That support proved invaluable for people like Charles Canida, President of Coal County Rural Water District #6, who said he was “overwhelmed” after missing the October 16, 2024, deadline. With Harmon’s help, he submitted the inventory and notices, and his system is now back in compliance.

“Everything,” he said, when asked what CU’s support meant. “We’re just barely operating above water.”

"I feel really good about it now, and I finally have peace of mind.”

PFAS Sampling

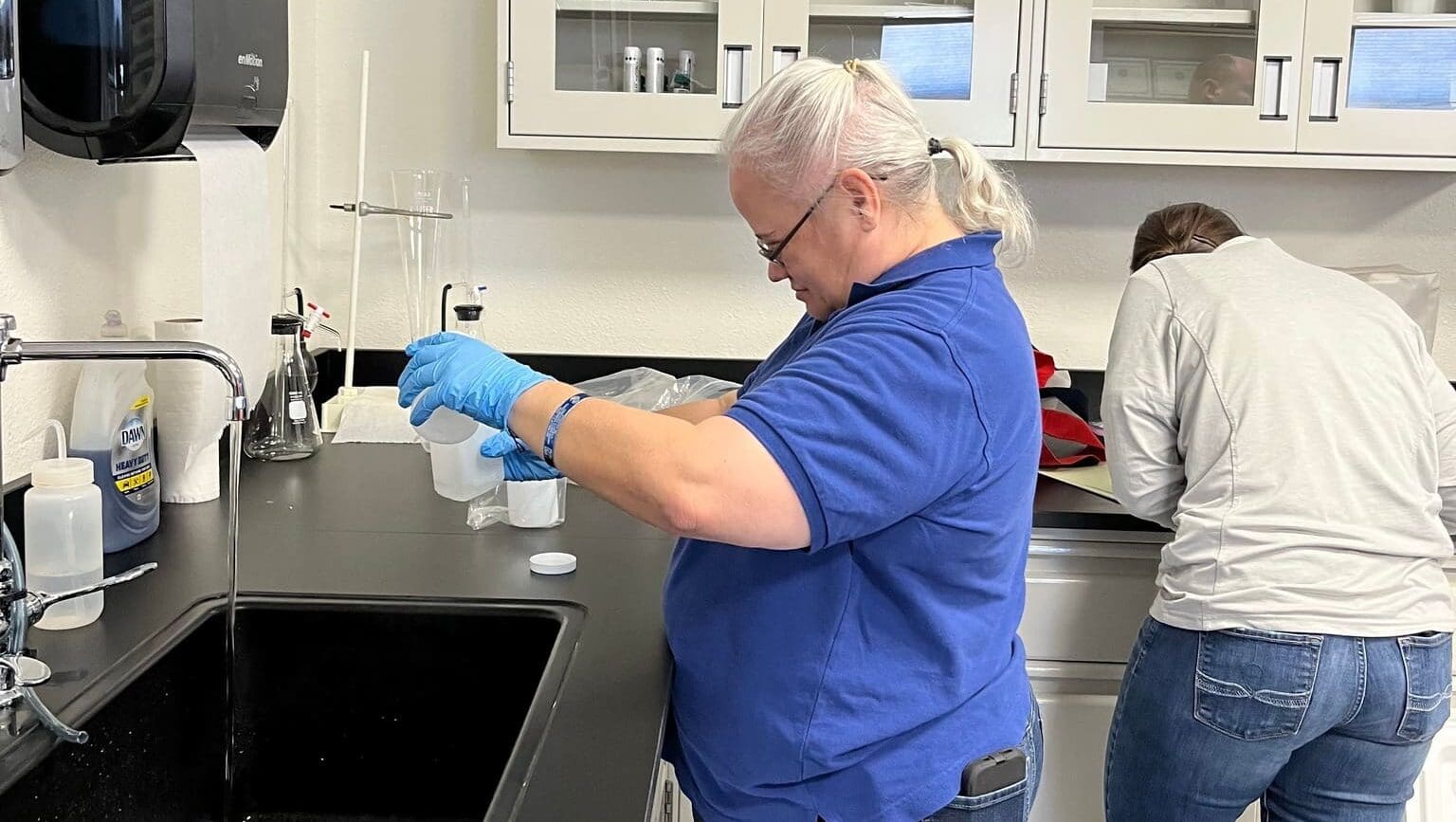

As the inventory work gained momentum, EPA expanded the subcontract to include PFAS sampling. ERG trained CU staff in specialized methods, and CU has since carried out collections at 11 tribal sites, with work now extending into Texas.

PFAS — per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, often called “forever chemicals” — are found in countless products, from firefighting foam used on military bases and airports to household items like nonstick pans. Over time, they seep into soil and groundwater, where they persist and accumulate. These chemicals are linked to serious health risks, which Hills said is why EPA has prioritized them under the Bipartisan Infrastructure Law. Early testing gives communities a critical head start: it shows what’s in their water and what needs addressing before regulations and treatment costs hit.

Staff must change gloves multiple times, avoid clothing or materials that could contaminate results, and carefully collect water before overnight shipping it to certified labs. Elevated results trigger follow-up testing and potential corrective actions — steps that can ultimately protect thousands of people.

“PFAS is an emerging contaminant and it’s going to be big in the future,” said Dan Cope, Wastewater Plant Superintendent for the Citizen Potawatomi Nation.

Tests at his plant showed PFAS levels above EPA’s new drinking water limit of 4 parts per trillion, with some wells reaching 16 parts per trillion — four times the federal standard. For the average person, that meant their tap water carried a potential long-term health risk.

Since then, Cope has adjusted operations to include more reverse-osmosis water, a filtration process fine enough to strip out these “forever chemicals.” The result is “non-detect” levels — so low the lab can’t even measure them — meaning the water coming out of the tap is once again safe to drink with confidence.

“Safe water is everything — it’s life.”

— Dan Cope, Wastewater Plant Superintendent for the Citizen Potawatomi Nation

Building Trust

For CU staff, the technical work is only half the job. Oklahoma State Coordinator Lucas Guinn emphasized that relationships are the key.

“Especially with Tribal systems, people can be reserved about outsiders,” he said. “You have to earn trust before you can even start pulling samples.”

That local trust is exactly why ERG sought CU as a partner.

“It’s not the same as having a voice on the phone from D.C. or Boston,” Hills said. “CU’s role was critical in that success.”

Long-Term Impact

What began as a compliance task has grown into something larger: a push to build long-term capacity. Systems once buried in paperwork now have tools to stay on track, while CU staff are building expertise in lead and PFAS response that they aim to replicate across their seven-state Southern footprint.

“This is a three-year contract, and we’re now in the second year,” Hills said. “We’re looking forward to continuing to tap into CU’s strengths — whether that’s technical work, sampling, or outreach.”

“It’s been a strong and effective partnership, and we’re excited to keep building on it.”

And just as staff at Jones Academy uncovered answers buried in old boxes of maps, this partnership between CU, ERG, and tribal communities is unearthing something deeper: the knowledge and trust needed to protect clean water for years to come.