This piece discusses maternal and infant loss, postpartum health complications, and the obstacles families face when care isn’t accessible. These topics are deeply personal and can be painful to read, especially for those who have experienced birth-related trauma or loss.

I lost my son, Ethan, in 2023. When the Broadband Expansion and Accessibility of Mississippi (BEAM) office invited the Broadband Team at Communities Unlimited (CU) to explore how something as simple as a strong internet connection could prevent tragedies like his, I knew I wanted to lead the project. I want to shine a light on a crisis that many people misunderstand, but I also know how difficult this subject can be. Please take care of yourself as you read, and step away if you need to.

When people talk about health in the United States, we often hear worrying headlines about pregnancy and childbirth. You may hear that the U.S. is one of the most dangerous wealthy countries in which to have a baby. But what does that really mean? It means babies in the United States pass away at higher rates than in other high-income countries, according to the American Journal of Managed Care.

It also means that far more mothers die from pregnancy-related causes in the United States than in other wealthy countries, the Commonwealth Fund and U.S. News & World Report released. And while these numbers describe the nation as a whole, the situation is even more serious in places like Mississippi, Louisiana, and Arkansas.

In Mississippi, children are nearly three times more likely to die before age five than in Massachusetts. And while families of every background are affected, Black mothers and babies face much higher risks than others.

There are many reasons behind these outcomes — including chronic health problems, limited access to health education, and economic challenges. But one of the biggest issues is the lack of doctors in rural areas. Many communities do not have enough OB-GYNs (Obstetrics and Gynecology) to provide prenatal care, or specialists who treat high-risk pregnancies.

These challenges are part of what experts call the social determinants of health — the everyday conditions that shape whether people can stay healthy. Things like income, transportation, where you live, access to food, and the ability to get medical care all play a role.

This is where broadband becomes important.

Today, reliable internet is no longer just a convenience. It affects nearly every part of daily life — including health. That’s why experts now call broadband a “super social determinant of health.” When families have strong internet access, they can use telehealth, reach mental-health services, find trusted medical information, and get support when they need it.

When they don’t, those options disappear. During pregnancy and after birth, that lack of access can have serious consequences.

Dr. Teresa Baker, MD, FACOG, and Co-Director of the InfantRisk Center at Texas Tech University Health Sciences Center, spends her days working to fill the gaps created by “maternity deserts” — regions with little or no access to specialists. Even from a mid-sized city, she relies on broadband to consult with rural primary-care providers, translate complex medical information into action, and help ensure pregnant patients get appropriate care.

One of those rural providers is Dr. Mary Williams, DNP, FNP-BC, who serves patients at Urgent & Primary Care of Clarksdale, Mississippi.

“Broadband is more than technology — it’s access. In rural communities, it allows expectant mothers without nearby OB-GYNs to connect to essential prenatal care, and it ensures that anyone, no matter where they live, can receive timely mental health support when they need it most.”

— Dr. Mary Williams, Urgent & Primary Care Clinic of Clarksdale, MS

Communities in the Mississippi Delta — places like Clarksdale in Coahoma County, Bolivar County, and neighboring Phillips County in Arkansas — are all Broadband Communities within the CU service region. With stronger connectivity, families there could monitor pregnancy complications from home, receive immediate guidance when something changes, and reduce emergencies that often stem from delays in care.

The need does not end at delivery. Infants can decline rapidly, and a single hour can mean the difference between hope and heartbreak. Postpartum, mothers face one of the most dangerous periods of their lives, when mental-health intervention is often urgent and in-person providers may be nonexistent.

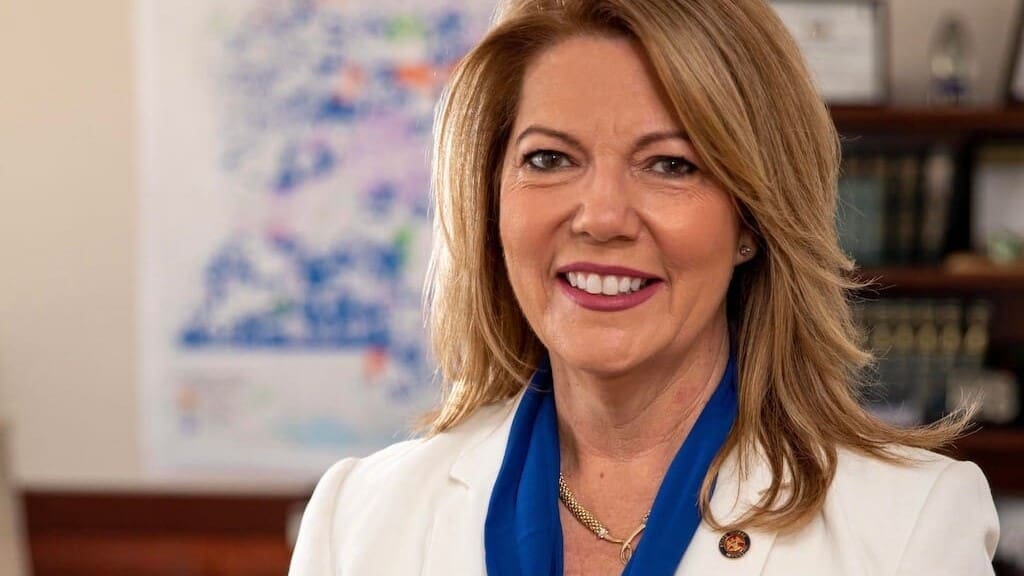

Sally Doty, Director of the BEAM office, understands that urgency in a way no policy briefing could teach. She lost her niece to a postpartum complication in 2020. Broadband, to her, is not a convenience — it is a path that can prevent families from suffering the same pain.

“Expanding broadband access isn’t just about gaming or social media videos — it’s about saving lives,” Doty said. “In Mississippi, where too many families still face heartbreaking losses from infant and maternal mortality, telehealth and connected care can be the difference between hope and tragedy. My niece lived in a large metropolitan area with connectivity, but many expectant moms do not. As we work to connect every unserved community, we carry their stories with us — because every mother and child deserves the opportunity to thrive.”

CU’s Broadband Team sits in the gap where infrastructure, education, and real-world needs intersect. We don’t sell internet service, and we don’t lay cable. We walk into rural communities that have been overlooked, listen to the barriers they face, and help them build sustainable solutions.

That can mean guiding local leaders through the technical maze of broadband planning, helping them secure state or federal funding, or bringing providers to the table when the community has no leverage of its own. It can also mean working directly with residents so broadband adoption isn’t a top-down mandate, but a community-driven effort rooted in health, opportunity, and dignity.

In towns where doctors are far away, hospitals are closing, and young families are doing their best to survive, a reliable internet connection can be the difference between isolation and care. Broadband alone cannot solve every challenge tied to maternal-fetal health in the South, but it is a powerful start — and one of the most practical tools we have to give mothers and babies a fighting chance.