In northeastern Oklahoma, representatives from a dozen water systems, an engineering firm, a tribal government, and a nonprofit are evaluating a proposal that could reshape how an entire county gets its drinking water.

The idea of regionalizing water — bringing multiple small, often struggling systems together under one shared treatment plant to improve reliability, quality, and efficiency — sounds straightforward. But as this group knows well, it’s anything but quick.

Regional water projects can take years — sometimes decades — to move from concept to construction. And in Nowata County — located entirely within the Cherokee Nation Reservation — 12 independent water systems are considering joining forces under a single $74 million regional plant, a process that could stretch as long as 10 years.

"This is a long process. Even if it was only one entity and one voice, the process of designing, engineering, permitting, funding, and building a water treatment plant is a long process. When you add the regionalization piece on the front of that, it can add a few years additional.”

— Billy Hix, Senior Director of the Environmental Health & Engineering Program for the Cherokee Nation

A Vision Rooted in Collaboration

The Cherokee Nation initiated the effort roughly 18 months ago after identifying Nowata County as an area where multiple small systems were struggling to sustain themselves. With support from the Oklahoma Community Infrastructure Team at Communities Unlimited (CU) — including Special Projects Area Director Gaylene Riley, Central Regional Area Director Julie Hudgins, and State Coordinator Lucas Guinn — the Tribe began exploring whether a unified, county-wide water system could provide stability for generations to come.

“We’re in the early stages, but this is where the real groundwork begins,” Guinn said. “Our goal is to help Nowata County, and its water systems find the best long-term path forward — one that ensures reliable service and strengthens the foundation for future growth.”

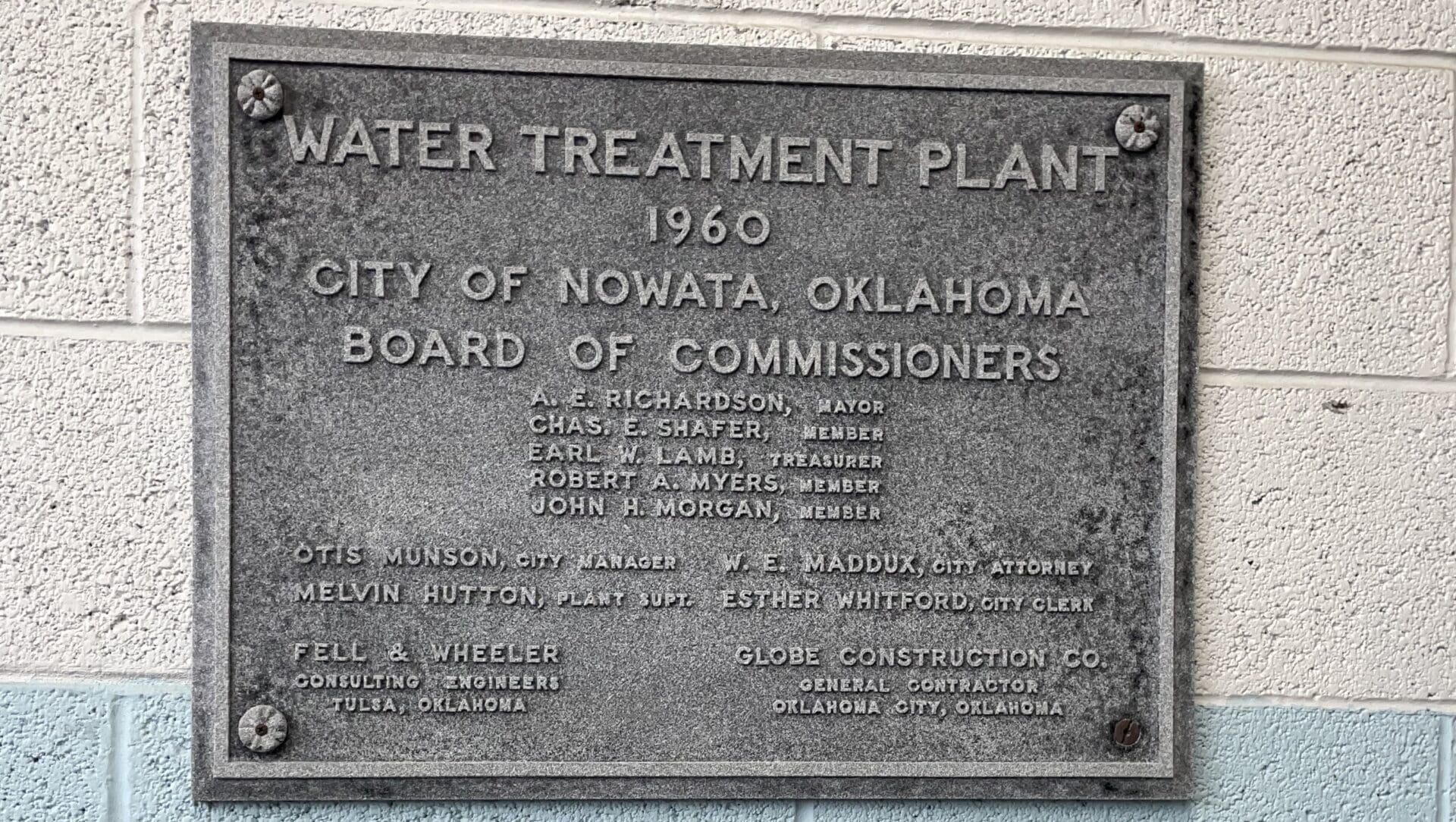

Many of the participating systems are small, underfunded, and operating aging treatment facilities.

“Some of them are very, very small,” Hix said. “They’re trying to run a water treatment plant to provide water to just a handful of homes and meters, and it just really isn’t cost-effective.”

After receiving approval from the Cherokee Nation Tribal Council, the Tribe allocated a portion of its American Rescue Plan Act (ARPA) funding to commission a county-wide feasibility study. A Request for Qualifications (RFQ) was issued, and Kimley-Horn — a national engineering firm with prior experience in Nowata County — was selected to lead the study.

What the Study Found

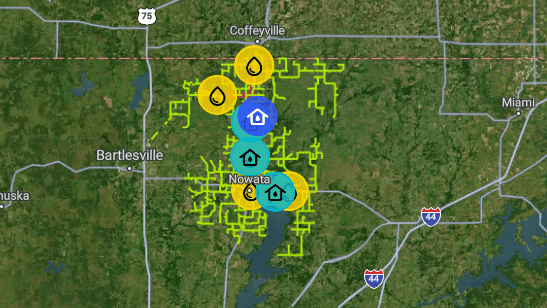

The study proposes constructing one centralized, roughly four-million-gallon-per-day treatment plant drawing from the nearby Verdigris River. The plant would serve about 10,000 people and 5,000 service connections across 12 systems: Nowata Municipal Authority, Nowata Consolidated No. 1, Rural Water Districts No. 1, 2, 3, 5, 6 and 7, Elm Bend, and the towns of South Coffeyville, Delaware, and Lenapah.

Olivia Bunch, Civil Analyst at Kimley-Horn, said her team began the feasibility study by gathering data from each water system in the county — including audits, water loss figures, operating costs, and maps — to assess current conditions and future needs. She added that the regionalization study builds on this information to evaluate how systems could work together under a single regional authority, taking into account demand, water loss, and environmental impacts.

The team examined three alternatives: rehabilitating the existing Nowata plant and building a new facility in the north; constructing one new ~4 MGD plant to serve the entire county; and building two plants (north and south) while bypassing rehabilitation of the existing plant.

Each option was scored for land availability, source water, acquisition needs, and cost. The preferred alternative was clear: one centrally located treatment plant supplying all 12 systems.

“A big part of this work is communication and making sure every system has a voice,” Bunch added. “We’re not in design yet — the goal is to understand financial feasibility first and eventual wholesale water rates.”

According to the study, the total project cost is estimated at $74 million. If funded entirely through loans, wholesale water would cost around $9.75 per 1,000 gallons, meaning that’s the rate needed just to cover repayment and operations. Grant support could lower that number — but in today’s funding climate, those dollars are increasingly competitive.

To prepare, each system is being encouraged to adjust rates now to ensure future sustainability.

Bringing the Public into the Process

Transparency has been a hallmark of the Cherokee Nation’s approach. Kimley-Horn is using its Public Coordinate platform — an interactive online map displaying the proposed alternatives, figures, and appendices — to gather comments from system operators and residents alike.

“The platform allows communities to go online, review the study, and submit comments or corrections,” Hix said. “It’s possible the engineering team may have worked with outdated or incomplete data, and this process helps get those details right.”

The engagement period, which runs through early January 2026, gives water systems time to share information with their customers for public review and feedback. Once that window closes, the engineering team will incorporate the comments, finalize the report, and meet again with all participating communities to determine next steps.

What Happens Next

Once the study is complete, each participating system will be asked to decide whether to join the regional effort. Hix said the team will meet individually with every system — meeting with boards of directors for rural water districts and with town councils or public works boards for municipalities. Together with the engineers, they’ll review the findings, answer questions, and formally request each system’s decision on whether to participate in the project.

Those that agree will sign a letter of intent to join a new Nowata County Regional Water Authority. The Cherokee Nation will then assist in securing legal and financial guidance to form the authority.

Hix explained that in similar projects, the Cherokee Nation has often helped fund the early stages of development. He said the Nation typically partners with organizations like Grand Gateway Economic Development Association — one of Oklahoma’s regional councils of governments that supports local infrastructure and community planning — to act as an interim administrative agent until a new regional authority is legally established and has its own governing board.

Once that authority is in place, the next phases — securing water rights from the Verdigris River, obtaining funding, and completing detailed design — can move forward.

Inside the Feasibility Process

Bunch said the study was designed in a Funding-Agency Coordinated Template (FACT) format so the eventual authority can move quickly into grant and loan applications.

“We reviewed audits, water-loss information, O&M (Operations & Maintenance) costs, sanitary sewer availability, and system maps,” she said. “The report maps the project area, includes population and growth projections, and builds a funding-ready case for implementation.”

In parallel with community engagement, Kimley-Horn and the Cherokee Nation are coordinating with CU and potential funders to align grant and loan strategies. Once the authority is established and water rights are secured, survey and detailed design work will begin.

“Realistically, it’ll take about two years to establish the authority, secure water rights, finalize the plan, and organize funding, plus roughly a year for design. That puts breaking ground around four to five years out. A full buildout — treatment plant plus transmission interconnects — could take closer to a decade. That timeline is typical for a project of this scale.”

— Olivia Bunch, Civil Analyst at Kimley-Horn

Why Regionalization Matters

Many rural systems across Oklahoma face aging treatment plants, limited budgets, and tightening regulatory standards. A regional authority can consolidate major operations — treatment, water sourcing, and transmission — while allowing each local system to keep managing its own distribution network.

Shared treatment means better water quality, stable wholesale costs, and reduced maintenance burdens on small utilities. The Verdigris River also provides a high-quality, long-term source that would otherwise require significant upgrades at each local facility.

“Having one reliable water source that meets standards would benefit everyone in the county,” said Ethan Cummings, operator for the Town of Delaware and multiple rural districts.

“All of our water treatment facilities are extremely old,” added Spike Howerton, superintendent for the Town of Lenapah. “With all the new regulations and compliance requirements, it’s hard for small systems like ours to properly treat water and make it aesthetically pleasing. The costs are just outrageous.”

A Long but Worthwhile Journey

Hix ties the effort to a Cherokee value known as Gadugi — working together for the greater good.

“That’s really what it’s all about. It’s getting all those communities and all those people to come together and see beyond just their own needs.”

— Billy Hix

As the feasibility report moves toward completion and resolutions are prepared, one thing is clear: progress in Nowata County will be measured not in months, but in milestones.

For the communities depending on clean, reliable water, the long road ahead is a journey worth taking.